The Backdrop

Over the last two decades the Metro Rail Projects have been the most touted and visible harbingers of change in the urban Indian landscape. Motivated to curb pollution and improve the standards of public transportation, the government of India developed overhead and underground metros across ten Indian cities, Delhi, Gurgaon, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Kochi, Kolkata, Chennai, Jaipur and Lucknow, at a remarkable speed.

The metro has even been particularly successful in the cities of Kolkata, Delhi and Chennai, with over 80% of travelers choosing the metro to travel over long distances (more than 10 kms; Goel & Tiwari 2014). Nevertheless, despite being much celebrated and acknowledged by citizens, the metro has not become an integral part of their daily travel routine as its acceptance in this context has been limited.

The Brief

Prepping for life post-Covid, we were assigned the task of deciphering how to make metro travel a part of an urban Indian’s daily travel routine.

An Exploration of Context

Step 1: Identify the key stakeholders

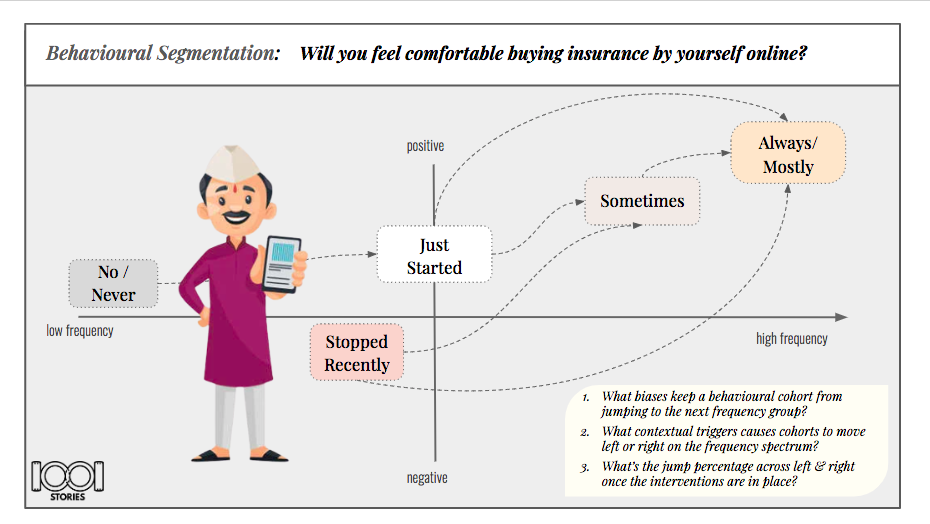

Metro Adopters, Metro Discarders & Metro Tourists

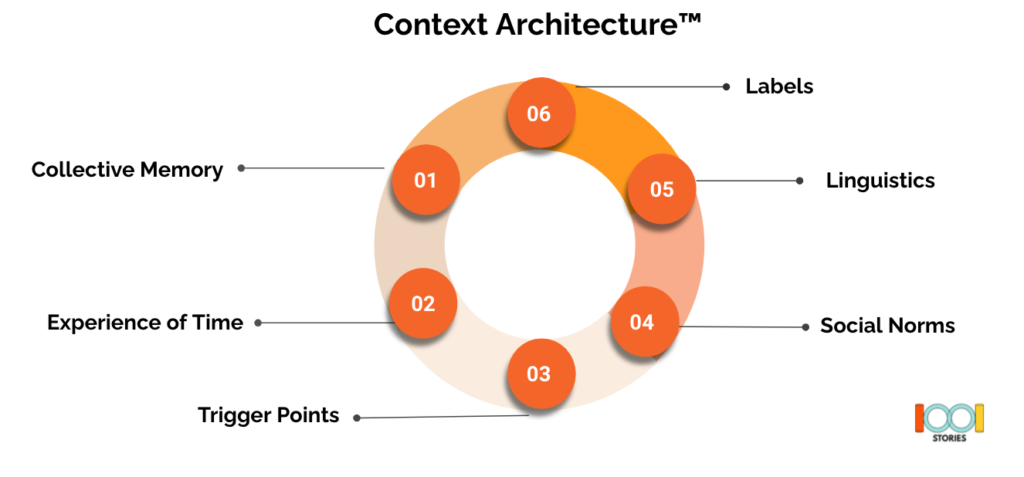

Step 2: Mapping the architecture of their context

Collective Memory Narrative: a mapping of motivation

Collective labels and roles: a mapping of identity

Collective experience of time: a mapping of goals/incentive intervals

Collective linguistic boundaries: a mapping of associations and interpretations

Collective trigger points: a mapping of existing collective nudges

Collective social norms: a mapping of behavioural patterns

The Navigation

We set out to study metro behaviour and commuter interaction across 4 cities using the following methods:

- Academic and government research

- Social listening on YouTube, Twitter and blog posts regarding urban Indian commute

- Projective techniques and interviews with users and non-users

We then mapped our learnings onto metro acceptance, associations, triggers, system barriers and commuters’ subjective well-being (will get to the reason soon).

The Findings

- The Context of Travel

Social Norm I Collective Memory

- Across interviews, the daily travel journey emerged to be a back-and-forth round trip between the home and the workplace. As expected, participants reported that they would like to travel quickly and cost-effectively. They further acknowledged that, contrary to popular perception, metro travel is not too expensive, and it most definitely is quick.

However, at this point, we encountered hesitation. When asked “would you then choose the metro over your daily mode of transport (train, bus, car)?”, participants replied, “umm………. sure I guess but in the local (train) I have friends I meet daily and I get to listen to music.”

Rationally speaking, their rejection of the metro should be influenced by their reluctance to change their default mode of commute. However, the ask for social bonding and zoning out were their vocalized preferences.

To take this investigation a step further, we asked participants to document a day in their lives in as much detail as possible. (An auto-ethnographic account; refer to Appendix Figure 1).

An analysis of the auto-ethnographies suggested that each one of us divided our day into moments of high involvement followed by moments of diffused living. The reconstructed episodic memories were most detailed for the high involvement moments, such as planning the next day before bed, when working and spending time with family.

In contrast, the moments of diffused living were marked by poor, generalized recall. These moments included shower time, breakfast and travel time. The moments of transit were being utilized by participants to cool-off and prepare for the next part of the day.

“We humans live well enough and long enough, to generate all sorts of stressful events purely in our heads.”- Sapolsky (2004)

Observations from the interviews and auto-ethnographies documented that commuters use their travel time as a break during which they can read a book, eat a snack, listen to music, socialize, pursue hobbies and even sleep. In this way, they allow their mind to wander and their bodies to physically achieve homeostasis balance. As far as daily-commuting is concerned, the moments of diffusion experienced during travel also help the commuter transition to their next identity role (supported by: Legal J-B et.al. 2016).

The experience of daily commuting offers important moments of diffusion, thus dictating our mood and ability to transition to and meet the demands of our identity role successfully. Research also suggests that:

b) Familiar versus Unfamiliar. While examining the modes of transportation in urban India, three different ways to travel emerged, each for a specific audience. While the local train and bus are associated with the masses, the metro is strongly associated with white collar office professionals and the rickshaw is uniquely positioned to offer a private experience via a public mode of transport. In fact, the bus has become the preferred mode of transport by 90% of daily commuters (in all cities except Mumbai, where the local trains dominate).

While evaluating the experience of bus travel (and local train travel in Mumbai), we learned that the link between the metro and the social group associated with metro travel is deeply rooted in western individualistic habits. This appears in India perhaps due to an inheritance of colonial expectations of behavior in a western context or an exposure to travel scenes from the global north-west. In contrast, the local bus and rickshaw are deeply rooted in community-spirited interaction, typical of the Indian collective consciousness.

The metro context, simply put, is ‘Unfamiliar!’ Increased ambiguity associated with this mode of transportation reduces sense of control and comfort – a situation to be avoided unless necessary.

The Translation to a New Problem Statement

One could say that the analysis of the metro context was a metaphorical application of the phenomenon of the Uncanny Valley (Mori, MacDorman & Kageki, 2012), only in this case with respect to contextual infrastructural upgradation. Infrastructural upgradation is appreciated until it becomes discomforting and stress-inducing. Perhaps at that point, the commuter seeks to travel swimmingly in order to maintain travel as an experience of diffused moments, thus feeling in control, in safety and within their familiar zone.

- The Context of Metro

Experience of Time I Labels I Linguistics

To further investigate the above hypothesis, we carried out a series of quasi-experiments to understand what makes the context of the metro unfamiliar. We generated three key insights:

- The Speed: We asked participants to tell us when the metro’s speed was appreciated and when it was not. They reported that metro travel becomes a pleasurable experience when it reduces travel time for long journeys and when traveling takes place in a non-crowded, air-conditioned bogie allowing one to view their city from an elevated position.

However, in some cases, speed hinders one’s ability to engage in travel rituals, such as listening to music, sleeping, engaging in conversation during daily and shorter-distance commutes. The multi-modal nature of travel to reach and depart from the metro station further reduces the perceived duration of the metro ride and thus of the delightful experience of being in the bogie.

“Metro is super-fast. Eastern-to-western side of the highway, otherwise takes a lot of time. From up high, I only see the city as beautiful. But to take the metro is too much effort for 2 minute AC” – 58, male, Mumbai

Solution Direction: Create a sense of seamlessness across the multiple modes of transportation to make it feel like a single journey and reduce effortful friction points, pre and post metro-experience. This will enable the commuter to think of their journey as one experience, giving them more time to experience moments of diffusion without feeling that ‘additional attention is required’.

Who is the metro for: We asked participants to observe a collection of photographs and identify people who they are likely or unlikely to see in the metro. Their answers confirmed the idea that the metro is perceived as the go-to mode of transportation for white collar office employees and college students.

The association between the metro and this alienated crowd was further enhanced through the linguistic and visual design. Respondents felt that the flavour of the local vernacular was missing from the metro environment – on the inside, it does not feel like it is part of the city. The colours, visual elements and instructions are culturally alien to the Indian commuter. Minimalist, geometric art and bodies without faces are unfamiliar and their messages are hard to understand.

“Why is English speaking smart? Why not French? And why not Bengali? In the metro everyone is saying, ‘Excuse me?’ ‘Pardon me!’ ‘May I sit here?’ It is hilarious!” – 47, male, Calcutta

Solution Direction: Change the context of the metro to create a sense of familiarity, ownership and accessibility ‘for all’ instead of making commuters feel that the metro is only for white collar office employees. Embrace and celebrate the local ethos of various suburbs by embedding it into the associated metro stations. Make everyone feel accepted by adjusting the weightage of the vernacular and English.

- The Map of the Metro: When choosing how to travel on a daily basis, commuters display strong ambiguity aversion. People are most comfortable when they find themselves in familiar environments, where routine scenes play out before them. They make decisions about commuting that will reduce their ‘Travel Anxiety’.

Eg.: Taking an Uber instead of driving to an unfamiliar part of town or taking the same train/bus everyday as a routine, falling asleep and knowing exactly when to wake up to get off at the right station.

These spatial familiarities are built over time, and rely heavily on the myriad of natural variations of a city, which changes every few kilometres. Being able to see the city and familiar landmarks gives the commuter a much-desired sense of control and visibility. The Google Maps habit and an Uber driver’s constant visual display of the map allow a degree of control over the journey, even on unfamiliar ground.

For travel to be joyful, you must know where you are, every step of the way.

With respect to the metro map, people are unable to decipher the map in relation to their understanding of the city.

Commuters have a mental map of their city that is experiential, with its level of detail being determined by the extent of their travel experience. The map of the metro, however, is removed from the city map making it harder to be processed and memorized. 73% of the metro maps drawn by respondents were depicted with minimal detailing and only included stations the commuters were aware of. “Metro map I know only airport road and Ghatkopar station. Airport road near office and Ghatkopar skywalk to switch to local.” -34, male, Mumbai

The metro allows for a limited view of the city, from a disorienting and unfamiliar vantage point above the streets, or under the ground. It is thus difficult to identify landmarks and have proper awareness of one’s spatial coordinates throughout the journey. As expressed by an occasional travel “From metro see a different city, from a top looks beautiful very different from when on ground”- 58, Male, Mumbai

Solution Direction: Encourage a sense of awareness by signalling control and reducing decision fatigue. For example, convey route clarity by superimposing the metro map on the city map, relook mechanism of function for smoother processes. Build a no pressure atmosphere for the commuter to relax.

The Context Architecture translated to Action

These findings imply that, for the urban commuter, travel beyond utility is an essential activity of the daily routine – an activity on which urban Indians spend a considerable amount of their time and money. The more seamlessly it integrates with and adds joy to the daily rituals of life, the more it enables the urban commuter to meet the demands of their daily life.

Along with a focus on speed, security, cleanliness and convenience, the metro environment needs to be redesigned in a way that it can offer an opportunity to serendipitously experience wonder, achievement, and relaxation. Additionally, each station should be integrated with its surroundings and its design could be inspired by the characteristics of its location. For example, Dadar metro station could be integrated with the flower market in Dadar, both visually and aromatically. Currently, localization of train stations is being adopted and experimented with in Delhi and Kolkata:

Similarly, introducing a mechanism that allows urban Indians to outsmart the system will introduce moments of joy and the feeling that it is ‘their own place’- “I have traveled in local without ticket so many times it is ok. Metro barriers cannot do!” -34, male, Mumbai. The feeling of endowment associated with being able to travel back and forth without being charged twice or watched creates a kinder interaction between the metro environment and commuters.

The ultimate goal of these interventions is to allow the urban citizen to feel both accomplished and at home in their cities, rather than aliens in an unfamiliar, rigid environment characterized by cameras, security systems and uncanny social influence exerted by the behavior of fellow commuters who are watching their every move.

References

(For extended list of references contact 1001 stories)

Goel & Tiwari (2014). Promoting Low Carbon Transport in India. UNEP. Link: https://unepdtu.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/case-study-of-metro-final.pdf

Pucher, J. & Korattyswaroopam, N. & Ittyerah, N. (2004). Urban Public Transport in India: Trends, Challenges and Innovations. 53. 42-47. Link: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294230520_Urban_Public_Transport_in_India_Trends_Challenges_and_Innovations

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. 3rd Ed. Henry Holt and Company. NY.

Legal J-B et.al. (2016). Goal priming, public transportation habit and travel mode selection: The moderating role of trait mindfulness. Link: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291148398_Goal_Priming_Public_Transportation_Habit_and_Travel_Mode_Selection_The_Moderating_Role_of_Trait_Mindfulness

Smith, O. (2016). Commute well-being differences by mode: Evidence from Portland, Oregon, USA. Journal of Transport & Health. 4. Link: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306344171_Commute_well-being_differences_by_mode_Evidence_from_Portland_Oregon_USA

Mori, M., MacDorman, K. F. & Kageki, N. (2012) “The Uncanny Valley [From the Field],” in IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 98-100. Link: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6213238

Kolkata & Delhi Metro. Links: https://www.hindusthanpublicity.com/west-bengal/metro-train-branding-kolkata; http://ms.npglobal.in/tdiinfratech//projects/retail/tdi-south-bridge/overview.asp?links=link1

Appendix A