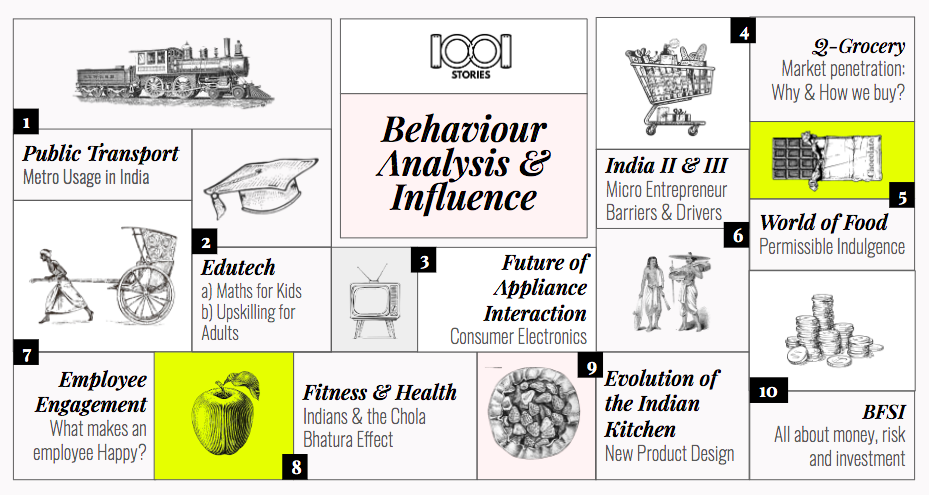

A Behavioural Science & Context Architecture Case Study on Auto Insurance by Pavithra Sudharshan, Poorni Suriyanarayanan and Rishima Shetty.

Part 1: The Challenge

From street vendors, to auto rickshaw drivers, and large fancy hospital staff, everyone in India today carries a QR code for payments through e-wallets. We can make every imaginable payment through our phones. Even the prospect of borrowing a loan has become more accessible and convenient – thanks to the massive overhaul of the Indian BFSI industry that fintech companies have set motion to.

However, insurance is one segment where the convenience of digitisation has staggered. The conventional offline mode of acquiring insurance has remained relevant among consumers who are otherwise comfortable managing financial transactions through a screen. A new breed of startups is trying to change this. Our client was one such digital insurance provider who caused havoc in a segment which was rarely shaken.

A new-age disruptor in a traditional network-led market, this particular fintech giant was successful in onboarding customers – with the exception of one particular cohort: the highly charged new car buyer. The ones who are glassy eyed with the prospect of gaining a new status symbol, somehow had evaded our client. This was a major problem as new car insurance is one of the more profitable verticals, with insurance being a mandatory requisite during car purchase.

Part 2: Understanding the context

To discern the barriers that hinder the consumer from purchasing the client’s product, we first conducted a deep dive into the cultural context of insurance.

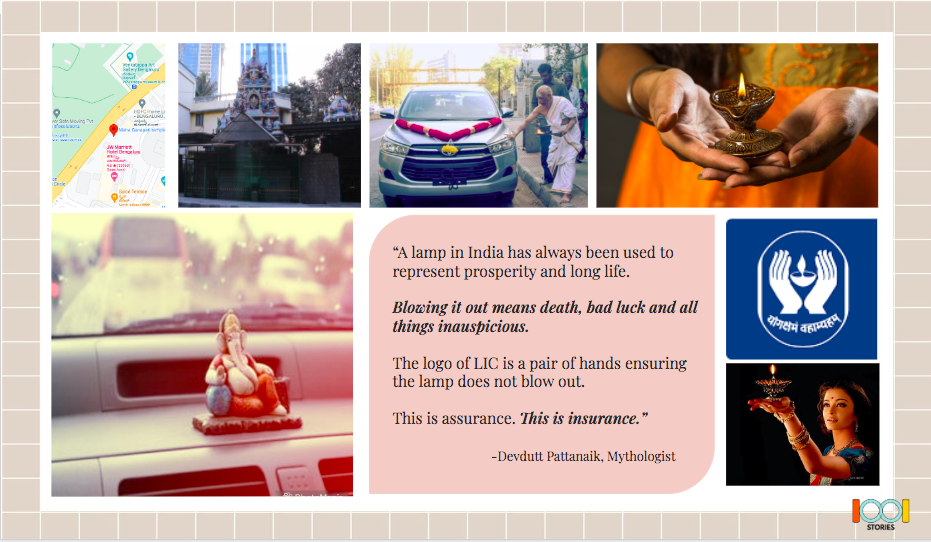

India’s understanding of ‘prosperity’ often differs from the rest of the world. Our historical reliance on an unpredictable agrarian lifestyle resulted in a fear of running out. It has become embedded in our cultural DNA to plan and save for the long term, despite having an abundance today. We ensure that tomorrow is taken care of by saving today’s surplus. It’s the hidden bundle of money inside the tin of rice/dal which allows the house to sleep peacefully at night.

Rituals and practices have existed throughout history to cope with our insecurity regarding the future. Security as a concept has always been a collective affair; people pooled their wealth together, and an authority figure who thought for collective well-being managed it.

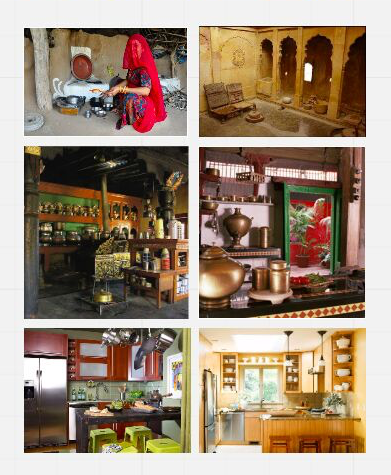

That has been our cultural association with insurance – where there was insurance, there was trust; there was always an authority.

Over the past few decades, as insurance became privatised and decentralised, the codes associated with it switched. Motives also changed, in the way the Indian customer perceives it, from ensuring overall welfare to making money out of the business. Since anyone could sell insurance, authority and trust were no longer expected from the category. Insurance became a ‘necessary evil’.

“Private insurance companies emerged in the Indian market as recently as in the year 2000. Prior to that, Indians flocked primarily to the public-sector LIC. Even today, people continue to place unquestioning trust in LIC and exercise caution when dealing with private insurers.” – Deepak Yohannan, CEO, MyInsurance Club (Aggregator site). Source

With inherent distrust in the system, insurance became a product that the consumer could not purchase without depending on an external authority. Therefore, removing the middleman out of this equation through digital insurance was unsettling to the consumer.

As we moved through preliminary understanding of the category, there were certain questions which become apparent to dive deeper into:

1. Lower price not good enough?

The client’s USP was their pricing. Having removed the middleman aka the car dealer who also sold insurance, there was no obligation for a commission – thus a much lower priced premium. In a country which takes pride in getting a good bargain, why does the lower price not attract this desired customer segment?

2. When does insurance become relevant in the purchase journey?

It was clear that insurance is part of a larger car purchase journey. There is great effort put towards choosing the colour of the car and immense joy in upgrading to a sunroof. The car is a marker of social mobility in the customer’s life, and the joy from this ‘upgrade’ takes precedence over other decisions, including insurance.

How can an insurance company effectively place itself so that the consumer can easily find it in the midst of a more important purchase journey?

3. The villainous car dealer (or is he?)

How can you pull the customer away from the authority figure, whom the customer has already trusted with the large, expensive purchase of the car and additional upgrades, and draw them towards another whole process which at first glance is less convenient?

Part 3: Research

We conducted extensive secondary research and literature review to uncover the biases and heuristics at play during insurance purchase. Having set the base, it was followed by in-depth interviews and projective techniques with participants, both users and non users of the client’s product. For the creation of a comprehensive purchase journey, we also conducted ethnographies by shadowing prospective car buyers as they went about the experience of becoming new car owners.

1. AMBIGUITY AVERSION

One of the primary findings through our research was the significant impact of Ambiguity Aversion during the decision making.

The insurance sector operates by relying on the consumer having asymmetric information. During the interviews, we saw that respondents parroted complex insurance jargon such as ‘bumper-to- bumper’, ‘Third party coverage’, and ‘Zero depreciation’. On further exploration, it became evident that there is little actual understanding of the words being uttered, but it allowed consumers to not deal with their lack of insurance know-how.

Just as the world pretends to understand web3 in 2022, Indians pretend to understand insurance. We learn a few words and use it as a shield to tackle the uncertainty.

This problem is amplified when we look at the pricing strategy used. When scores of other insurance providers are more expensive, the reference point of what is ‘normal’ is higher than the client’s premium rate. With this anchor in place, propelled by imperfect information and no toolkit to compare with, the client’s brand framed itself as ‘cheap’. With this framing, the consumer does not look at the insurance premium paid as value for money, rather is suspect of the quality.

Given this intangible, ambiguous and complex nature of insurance as a product, one can only hope and pray that their future claims are settled while paying relatively low premiums.

As the consumer becomes conscious of the insurance decision which needs to be taken, they begin to seek guidance from familiar sources that display authority to tackle the problem of ambiguity.

2. USER’S SPHERE OF INFLUENCE

The second finding was that the reference network of the individual and their experiences played an important role in bringing a brand into the purchase consideration set. Due to the nature of word of mouth, it does not occur at a particular time, but rather is a large knowledge base built over time. Positive anecdotes allow the brand to be a potential choice, while a negative anecdote is remembered harshly, thanks to our brain’s tendency to ruminate(East 2015). The latter is used as a strict elimination criterion. A story which says ‘Don’t’ has a notable effect on behaviour.

Our research also unveiled that the decision journey of car purchase allowed for the dealer to be a convenient authority figure during the subsequent insurance purchase. Insurance is a mandatory aspect of owning a car in India. As the requirement of this product has already been decided, there is a low cognitive effort which pushes the buyer towards the closest available authority figure. Having already created a relationship with the dealership during the purchase of the car, their recommendation for insurance is also blindly followed. While we initially believed the dealer becomes an active barrier, insights revealed that the real villain was the larger ambiguous system.

3. BUNDLING OF CHOICES

Our third finding, which we discovered by shadowing prospective buyers, was that the car dealership presents the insurance as a part of the larger car bill itself. This created the illusion that the insurance is not a separate product with its own purchase journey. The choice architecture is such that the big purchase of the car is bundled with additional requirements such as, road tax, registrations, insurance, etc., which the customer entrusts the dealership to sort out until the car is delivered.

4. BRAND ASSOCIATIONS

Finally, a crucial finding uncovered through projectives was that users of competition, i.e., traditional insurance brands, associated their choice of insurance with traits such as protection and pampering. This was in contrast to our client’s brand which was associated with traits like digital and paperless. In a country which is wired to equate prosperity to protection and surplus, the cues provided by insurance brands have to reflect these beliefs. Digital services are not a surplus, but throw in a nimbu mirchi (seven chilli peppers and one lemon strung together which is meant to protect from the ‘evil eye’) and we understand that we will be taken care of in the future.

Part 4: Behavioural Interventions

To summarise, we understood that there were two key challenges that the client must address to achieve their objective-

- The product and the larger system were ambiguous. The consumer was not ‘insurance literate’ to fight this ambiguity on their own. Naturally, they leaned on the expertise of the closest authority figure available.

- Consumers are not enamoured by low prices in this segment. ‘Full coverage’ during claims was the primary concern; price was only a criteria for elimination during purchase. Trained to expect protection from the category, low prices equated to cheapness and poor quality of service.

In order to tackle the aforementioned challenges, we tested interventions for the client’s communication strategy, and presented the successful ones in the form of a guideline on how to frame their offerings. Some of these were related to:

1. FROM ‘LOW PRICE’ TO ‘RIGHT PRICE’

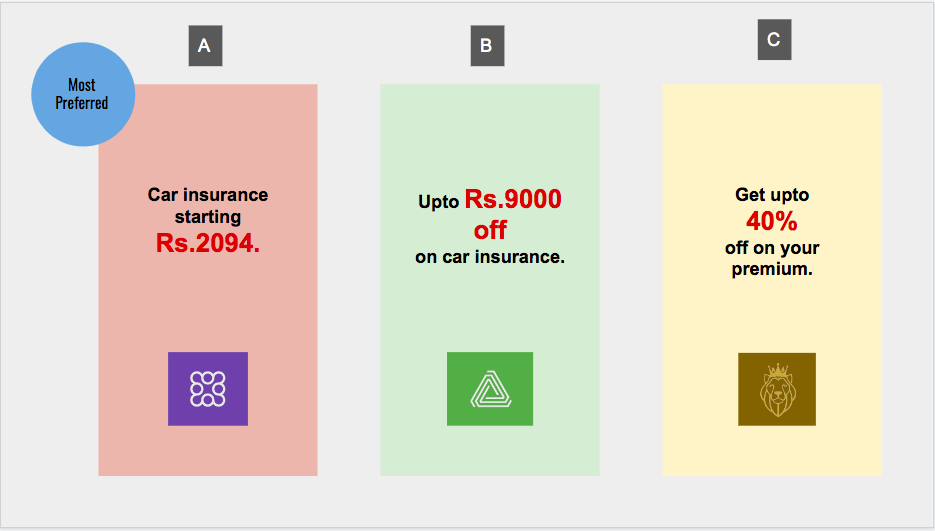

Currently, the consumer’s reference price was anchored to that of competition. A discount from this anchor can cue in ‘value’, but only when the discount is up to a certain point, a safe zone of sorts. In our experiments, further discounts from this safe zone triggered quality related anxieties. Hence, we proposed setting the client’s positioning at the ‘right price’ in the market, as opposed to being the cheaper alternative to competition.

2. DO VS. DON’T

Reframing savings to instil FOMO and trigger loss aversion in the consumer.

3. VISIBILITY IN THE CAR PURCHASE JOURNEY

Fighting against the rigid choice architecture presented in the dealership meant the client had to be visible and bookmarked by the consumer at the early stages of the car purchase journey. Bundling of the car price with the insurance in their mass and personalised communication messaging would resolve the same.

Insurance being a complex product in itself, only communication interventions would not suffice. A comprehensive audit of the user journey highlighted the multiple touchpoints that the consumer has with the brand.

The final deliveries were behavioural strategies and design related to the product (new offerings), brand (communications framework) and people (improving the customer touchpoints e.g. support executives, call centre scripts, and personalised messaging). The ultimate goal of these interventions was to reposition the client’s brand towards trust and authority, an image age-old companies have always projected.

Part 5: Results

The last update from the client revealed a 55 percent increase in customer engagement post the implementation of our interventions during test period.