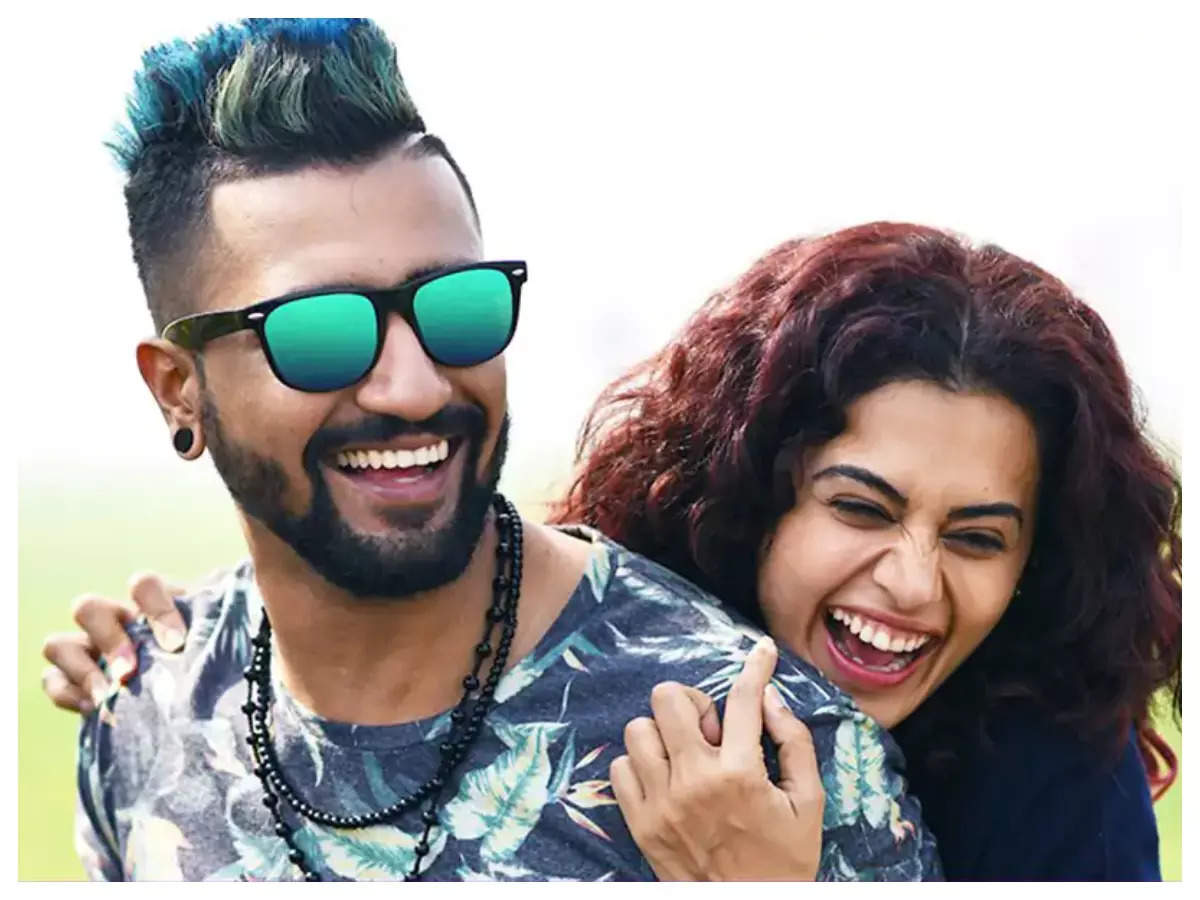

“Don’t get me wrong, I’m not anti-national or anything,” she started with, which was, trust me, confusing. What we were talking about lay far from the politics of ideology or veneration of the fatherland. We were talking about Vicky Kaushal’s hair-do in Manmarziyaan.

In the three years since we began the quest to understand what love means in India today, I’ve heard of many idols, from real life to cinema, who have influenced people’s idea of love. There have been over a hundred one on one in-depth interviews, including one that lasted over three days. Each was incredibly intimate and shockingly human, bringing to centre focus the sacred space a researcher shares with her respondents. There were moments we drew physically closer, talking in whispers and decoding pregnant pauses – remembering, romanticising, imagining. Full of false memories, old rage and post-rationalised histories, what mattered was not the truth- only that it lay bare. For those long forgotten fragments of old fantasies and unbridled access to their new evolution, I will be forever grateful.

One of my favourite stories from these interviews came from Vishal, a teenager in the 90’s.

“She was a very sweet looking girl. I used to look at her in the assembly and hope she wouldn’t catch me. She was very organised, and I remember thinking- yeh mujhme nahi thha (this I didn’t have in me).

Back then, my uncle had a Maruti Omni. I used to think ‘Badi gadi hai!! ( It’s a big car!)’ I didn’t know too much, my ideas were all very filmy. I imagined driving my uncle’s Omni filled with balloons and stuff… she used to wait at a bus stop nearby, and I thought, one day I’ll go with this Omni with balloons and pick her up, and when she gets in, she’ll see all this and know I’m proposing to her. It was just.. it made me so happy!

This fantasy featured the winning combination of a boy, his big car and the love of his life. When we looked closer, Vishal found that as original as his teenage dream proposal was, much of it was produced in Bollywood.

The Angry Young Man is the Most Eligible Bachelor

“In my parent’s time, heroes were all saving the village or fighting for the country. I think the idea of what makes a man ‘man’ was, could he lead everyone”, Shipra told me, over Zoom from Mumbai. Assisting in film production, she is an ardent film lover.

“And then there were all these films where one friend sacrifices his love for his friend. I never understood this. What man would do this? Why is this good? Or these heroes who would woo the girl and then some disability comes and then he tries to make her leave him because he doesn’t want to spoil her life.. A great man sacrifices for the good of the people around him, is what they would show. Even my mom would talk about this…. It was a virtue. And then came Amitabh Bachchan.”

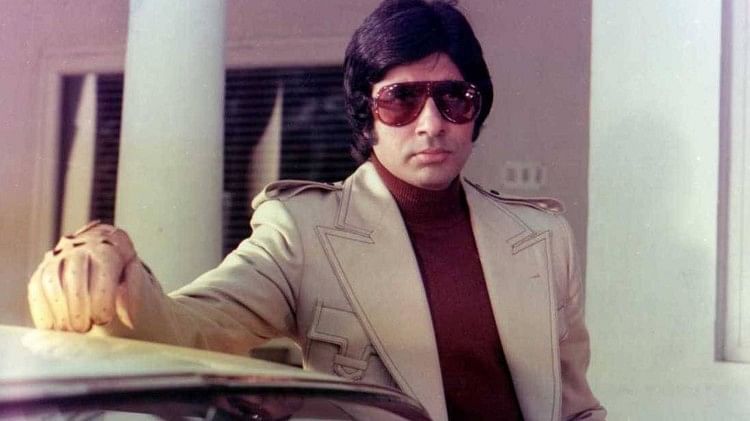

In numerous interviews, Amitabh Bachchan emerged as a clear marker to what came to be the new era of Man.

“Before Amitabh Bachchan there were many strong men… Dharmendra was an action star too, and also the older generation loved him in loverboy roles. Shammi Kapoor too, he was mainly a loverboy, wooing the heroine in strange songs and dances.”

When I look at the recording of this interview now, I can see the excitement in Vishal’s eyes as he launches into an ode to his idol.

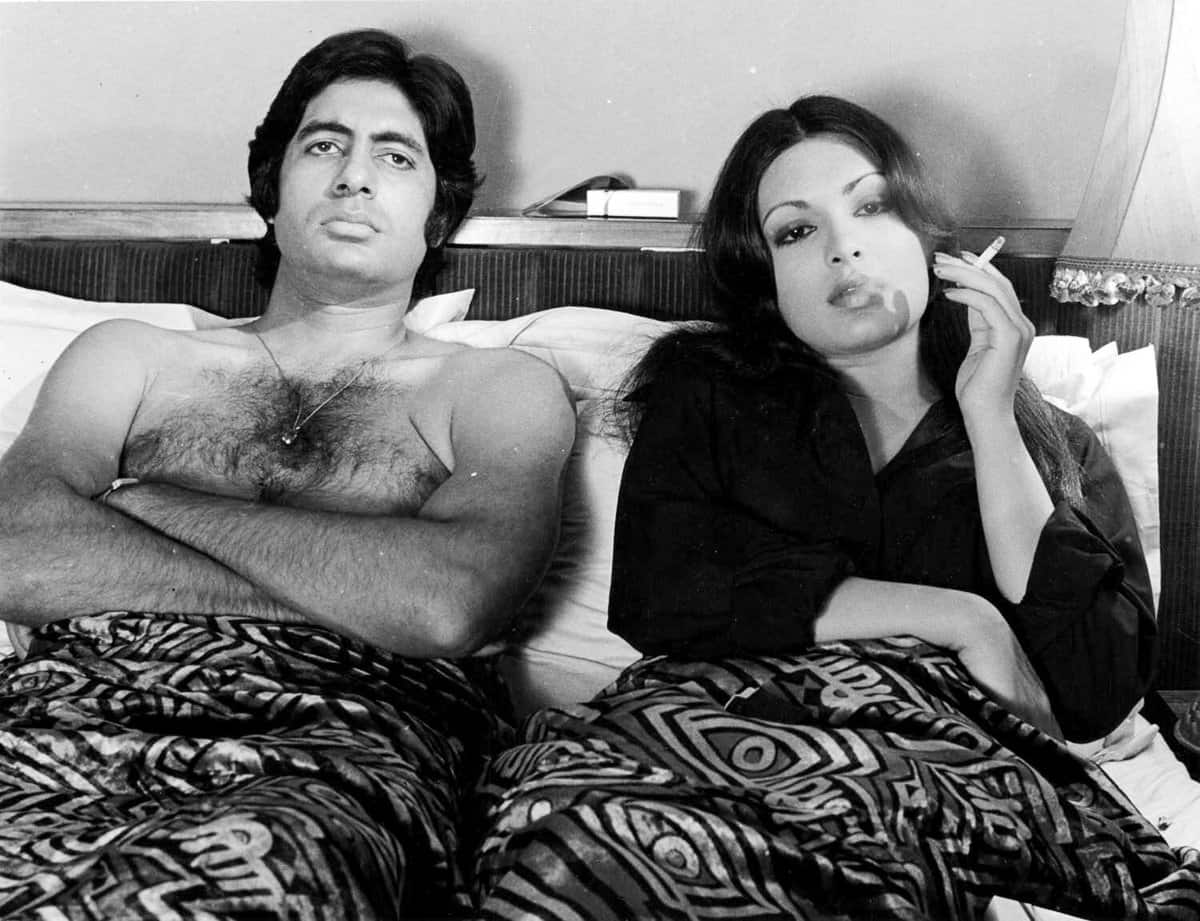

“Amitabh was the first time a man stood alone. For himself. Not for society, not for family, not for anything else but what he believed. First time, you saw a hero choose the wrong path to success. He didn’t play by anyone else’s rules. Even his heroines were not women jo maa ka khayal rakhegi. (Women who’d look after his mother) I mean.. they were also, in their limited role, very individualistic. Just like him.”

Shipra saw something similar in Amitabh’s stardom.

“Amitabh Bachhan’s films for the first time, we see the man’s man who does things for himself, without guilt. His revenge was personal, his love was personal. When he was doing humour, it was doing it in the mirror, talking to himself. He breaks the fourth wall and talks to us… I mean, that was what was a MAN, so comfortable with himself. It wasn’t an accident, he even did a movie called “Mard!”

In a collective society like India, Amitabh Bachhan’s portrayal of masculinity comes not a moment too soon. Per a 1986 Modelling Indian Migration and City Growth report by Charles M. Becker, Edwin S. Mills, and Jeffrey G. Williamson, India’s urban population between 1965-69 grew twice as fast as its rural population, indicating a massive rise in migration to cities. In a time where manufacturing jobs were most in demand, the urban landscape was populated by a new youth, uprooted from the comfort of societal embrace to compete, guide and relearn their norms. A newfound individuality surfaces, uninhibited by the supervision of an older, intimate world.

This new youth who had to fend for himself and learn to thrive in the big bad world was perfectly encapsulated in Amitabh Bachchan’s depiction of the man of the day.

So while the good son, Jeetandra’s Ravi, rides a cycle for 10 days at a stretch to win 10k for his father’s operation in 1986’s Ghar Sansar, Amitabh’s Vijay has already sorted out his gaadi, bangla and whatnot by 1975 in Deewar.

“Amitabh always had a car.” Vishal remembers. “I think that’s why I wanted to surprise that girl in an Omni by offering a lift in my big car. Today when I think of it, that would’ve been damn creepy. Plus, Omni is famous as a kidnapping gaadi!”

It will be a while before new codes of masculinity emerge and shed light on the unexplored facets of being a man.

Salman Khan, a boy in love.

“At some point, you had to love a girl.” Ganesh (name changed), a 45 year old professional from Hyderabad tells me. Growing up in Mumbai, he was talking about childhood, being a boy in the 90’s, and the time that one becomes aware that they have romantically checked in.

“As boys, your group will grow. You start with kids of the same age and then when you grow older, you’ll join older kids’. The fight up the pyramid starts there itself. You’ll look up to someone older, you’ll come to know they have a girlfriend. You’re like… that’s the next level.”

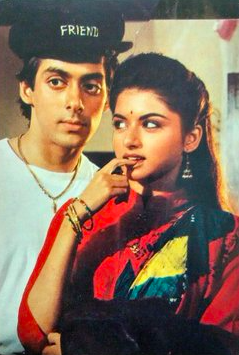

“In school and in our groups there is this idea of who you should be like as a boy, as a man. The older boys are teaching us, telling us how to be, not to be. And then, Maine Pyaar Kiya releases. Suddenly, the idea of who you should be as a boy changed!”

In 1989, Sooraj Barjatya took a bet with Salman Khan, who, if tabloids are to be believed, Barjatya felt was too ‘small’ for his lead role, ‘Prem’. He gave it a shot anyway, despite worries like actress Bhagyashree refusing to have Salman rub Iodex on her hurt knee, which is why they shot with a hurt ankle. Despite everything that is wrong with that last bit of trivia, the film, Maine Pyar Kiya (I have Loved), became a cult hit.

The film fetched seven Filmfare Awards from 13 nominations in 1990 and was dubbed in English as ‘When Love Calls’. It was the biggest hit in the Caribbean market at Guyana and also dominated the box-office at Trinidad and Tobago. The film was later also dubbed as ‘Te Amo’ in Spanish, catapulting Salman Khan to stardom outside India and turning him into an overnight sensation at home.

“In Maine Pyar Kiya, Salman is a boy and not the world, not the system, not anger, not revenge but it’s love that turns him into a man. It was so fresh! Suddenly left, right and centre in our group, boys were in love. Salman’s cap became so famous. Even I bought it!”

Salman Khan’s Maine Pyaar Kiya featured in conversation with 37 year old Varun as well. He remembered his first date in a coffee shop in Lucknow. Friends was on TV. New Baristas had begun to pop up in the city. Suddenly, there was a space specifically for young people to do things that young people thought young people did.

“If you liked a girl you had to ask her out. You get some more pocket money and go for a date and talk.” About what, I ask. He doesn’t remember. Then, he adds “You try to be friends. You can’t start with telling her you like her, right? You learn these things from the movies, from TV.”

“You be cool. You don’t rush. Salman Khan did it in Maine Pyar Kiya – he was first a friend and then they fall in love. But in my time, it was Shahrukh Khan.”

Find a girl who makes you want to love her like Shahrukh Khan.

I had the privilege of speaking with Economist and Author, Shrayana Bhattacharya and Director and Founder of Agents of Ishq, Paromita Vora in a panel on Love and Sexuality in India at the Now Fest, 2021. It was a conversation that turned romantic love on its back, to understand it more from the lens of an economic tool and its societal utility.

“I don’t think I’ve studied love, I’ve studied loneliness.” Shrayana says, when we discuss her brilliant book, Desperately Seeking Shahrukh: India’s Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence. The book covers ten years of interviews with women who make up the workforce of the country. They are far from the image drawn by the media – fighting beauty norms yet beautiful, empowered yet dutiful.

Shrayana says that these women are extremely lonely, and they’re working in an economy that does not want women to work. It’s an economy uncomfortable with them expressing desire, owning money and stepping outside the home. Less than a quarter of Indian women hold a job. When these women tried to stand on their own, they faced tremendous pressure and a withdrawal of love from their husbands and families. Economists, she says, have started calling these ‘Hidden taxes’. The cost of independence and embracing her feminine identity? Love.

“What I realised was that the reason these women loved Mr. Khan so much was that they were so unloved. They were looking for the joy in the love that he could provide – something that they really wanted in their lives!”, Shrayana adds.

A delightful excerpt from her book Desperately Seeking Shahrukh, that I’ve taken from HarperCollins, tells us the story of Lily.

Unlike most women working in India’s care economy, Lily had the privilege of a few certainties. She knew her employers would pay on time every month and she had a bathroom.

She also had access to a television. There was a spare television in a guest room on which she could watch shows for an hour each day. ‘I think my madam would let me watch for more time,’ Lily said, ‘but it doesn’t look good.’ Lily loved watching film songs, especially Shah Rukh songs. She used to hum them as she did her work and even taught her madam about Hindi films and Shah Rukh. Sometimes if she was slow or appeared not to be paying attention, her madam would joke that she was dreaming of Shah Rukh. I asked her why she liked Shah Rukh in particular. ‘It just happened,’ she said. ‘I saw him and I liked him the best. I get to see many heroes and many songs when we cut vegetables in the TV room, but he is the best. He seems like a good man, you know. He makes me laugh. Not violent like other action heroes. We never find time to watch whole movies because of work but they play his love songs all the time on TV, so I get to see him a lot.

Sometime in October 2010, during her daily hour of television, Lily learned of a Shah Rukh film bonanza in honour of his birthday. The channel advertised its plans to broadcast a film starring Shah Rukh every Sunday at noon for all of November. She wondered if her madam would allow her to watch these movies in their entirety. A week later, noticing that her employers were in a good mood, Lily asked her madam if she could watch these films every Sunday. Although her madam struggled to understand Lily’s interest in a Bollywood hero, she said it was no problem. Madam didn’t mind as long as Lily got her work done. The cook, who didn’t live with the family, said she would come earlier on Sundays to help Lily, and they planned to try and watch the movies together.

Lily was thrilled. She had both permission and a companion. Her happiness did stumble upon a moral dilemma—the Shah Rukh film festival clashed with church on Sunday. If she did not show up dutifully each week to pray, her family and the local priests would reprimand her. A month-long absence would be a sign of extraordinary defiance. Abandoning Sunday church would make her seem too high and mighty to other women in her prayer group. It would signal that she considered both the church and their company to be optional; that she did not believe in the power of prayer. But this was too good an opportunity to miss. She was never going to have the comfort of going to the nearby theatre. The tickets were too expensive and she would feel too guilty spending her money on the movies, even if she went to a cheaper hall. No live-in domestic worker went to watch films without her employer. It was a simple choice: Shah Rukh or Jesus?”

It is difficult to write about Shahrukh Khan and his impact on Indian gender roles, love or cinema, and keep up the semblance of objectivity. In his own words, the incredibly self aware actor once proclaimed in a packed auditorium in Vancouver, “I sell dreams and peddle love to millions of people back home in India, who all assume that I am the best lover in the world.”

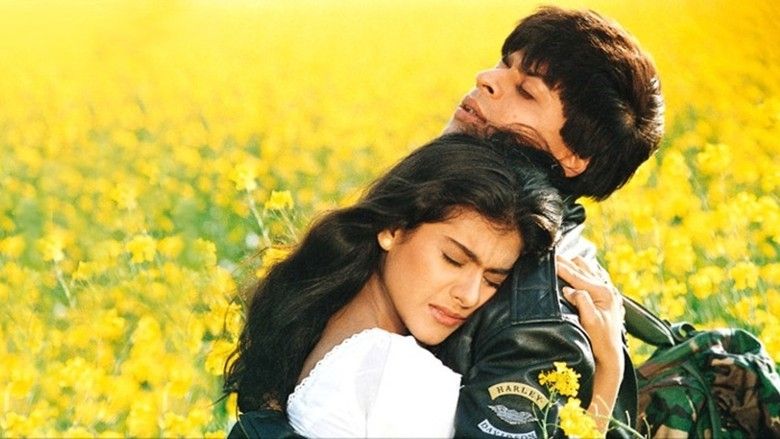

In a movie starring Shahrukh Khan, his co-stars become the loves of your lives. His Pooja is more beautiful than Madhuri Dixit is, his Simran is more loveable than Kajol could ever be. In being loved, in being the object of Shahrukh Khan’s attention, they are the focus of ours.

An off-beat review by Nitisha Gautham in the Quint, titled Pathaan & Burden of Beauty, summarises Shahrukh’s appeal and why he is so intrinsically linked to love.

Nitisha explains, “Shahrukh has been known to make his women shine. Whether it is Simran to his Raj or Tina/Anjali to his Rahul, there is a symbiotic relationship between him and the counterparts where everyone benefits. It can be safely said that it is not Deepika but John (who plays Jim in the movie) that Shahrukh has been paired with in Pathaan. They bring out the best in each other. And as the divine writ goes, Satan is always more attractive than any competition. It is not for nothing that there are moments of doubt and fear and admiration stirred by Jim in even Pathaan.”

Regional Indian Cinema had something else going on. “In Tamil films, a common trope is that heroes keep running away from girls. He’ll be a loafer, chilling in life, doing his own thing and then some girl falls in love with him and tells him she wants him to marry her. You’ll see him avoiding her like the plague. Then something happens and he has to save her, and then it’s like he’s committed. He has taken a responsibility. Now he’s a man. Even if he falls for a girl, it’s not like he’ll go up to her. He’ll get her attention somehow. That changed later, but it’s not gone far from that even now. A Tamil hero doesn’t go to the girl. The girl comes to him.”

Sankar, name changed, was 28 at the time of this interview in 2020. He remembered how he would see his father carrying all the bags when they went grocery shopping. Often, it would be getting late as his wife endlessly looked around for more deals in the market. He would be irritated, but would never complain. “I thought, that is the burden of being a man. That’s why the hero keeps running away!”

Reminiscing, he spoke about how films influenced his ideas around love.

“ I first had a crush on this girl in my school. She was very good in studies, so I would rattle her by beating her at studies or competitions. It was like she was my biggest rival! She was really angry with me and, I don’t know, that was fun! Come to think of it, even in my first job in Chennai, I had a crush on this girl and I just competed with her. She really had a problem with me, but we eventually became good friends.”

Why, I ask.

“It’s a curiosity, can I get her attention, or not? It has happened too, where once the girl pays attention, she likes me back and then things happen. But I would never let a girl know I like her first.”

Everywhere, cinema taught men to be men and women what to look for in them.

Where Amitabh Bachchan set the distinctive lines between man and society, Salman Khan gave the next generation a reason to tow it. Along came Shahrukh Khan with a new skill – How to look at a woman like he found the world. When he stretched his arms out in his signature move, he transformed every girl in his audience into a Simran looking for her Raj, and turned every boy into a Prem, looking to become a Raj.

The non-Anti-Nationalist finishes her story.

In 2020, my respondent was a 25 year old advertising professional in Bangalore.

“It was a lovely film.. Like not a typical love triangle, but very real. Nowadays, couples do anything they want. Anything goes.. It’s so rooted in how millennials behave in relationships. And Vicky Kaushal as a young, unsure guy who really loves this girl but he keeps backing out… he played it very well. Even his hair-do in the movie, it’s very over the top but he pulls it off so beautifully!

“Don’t get me wrong, I’m not anti-national or anything…” she said, breaking from her review of the movie. I was curious why her mind went that way.

From interviews with multiple doe-eyed worshippers of film, if anything was clear, it was that while art imitates life, Cinema instructs India. Cinema, in its exploration of love’s evolution, Indian masculinity and a recent love for depiction of femininity are still teaching India how to look at its boys and girls and the things they do when no one’s watching.

The trouble comes when even the idols begin searching for belief.

“This boycott this and boycott that… some of it is legit, I think. So many of these people have gotten away with so much sh*t just because they’re stars. And then there are these films coming out on patriotism or Indian greatness… and you know they’re just doing it thinking, I think now this will work.”

Something was disturbing her. We pushed on.

“See, like with Shahrukh Khan. People loved him because they knew what to expect. Or like Amitabh Bachchan, he was the Angry Young Man. There have been some very promising actors after that.. Vicky Kaushal is one of them. He’s a genuinely good actor. And then he did Uri. I watched it… it’s a good film also. People loved it. My mom was damn excited it played on Independence Day on TV. But.. I felt like… why ya. Why you also?”

We laughed for a while. In a genuine moment of connection, I could feel her heartbreak, when a star she was beginning to fall in love with, had fallen out of a character she assigned to him.

“He could’ve been the next Shahrukh, man. I just hope he does more of those roles.”