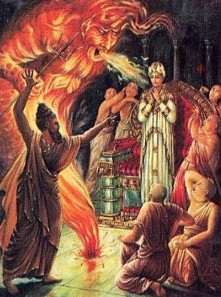

It was obviously difficult to accept defeat for Siva, Hindu Lord of Speech and the Truth, when he lost a debate. It left him in a truly foul mood. When his consort, Parvati, had had enough of his brooding and absent-minded muttering, she ordered him to go and get rid of his anger.

Siva remembered that the lovely and pious couple, Sage Atri and his wife Anusuya, had been praying long for the gods to be born to them as children. He paid them a visit, gifted them with this rather inconvenient, angry portion of himself, and happily went home. Anusuya and Atri were soon blessed with a baby boy with the great qualities of Siva, plus some more. A delicate hint, they named the child Durvasa — One Who is Difficult to Live With.

Stories from the Vedas, Upanishads and the Mahabharata tell us that Rs̈i Durvasa is a short-tempered sage with an aversion towards being ignored, for which he is known to enthusiastically curse people with horrible things. In the Vishnu Purana, he curses Indra because his elephant doesn’t like the flowers Durvasa gives him. In the poet Kalidas’ famed Abhijñānaśākuntala, the newly-wed Sakuntala is cursed because she is lost in thoughts of her beloved and ignores Durvasa’s greetings at her door.

Such terror befalls those who upset Durvasa, for he would huff, puff, curse and fracture their worlds unless they acknowledged him, gave into his greatness with eyes closed and open arms, and accepted him into their homes. Owing to the curse, Indra almost loses his throne in heaven and the universe has to be churned to regain it.

Sakuntala’s lover forgets all about her for a couple of years until off chance, a signet ring he sees brings back memories of their love — a remedial addition to his own curse, which Durvasa grants Sakuntala when he is in a better mood. Everyone thanks him immensely then, because it was him remedying his own curses that helped them recover from misfortune — which he had himself inflicted upon them.

But if that isn’t stupid, I don’t know what is.

As nature’s favourite animals, we have accomplished the great feat of sidestepping the food chain and inventing our own measure of social hierarchy. Of our many yardsticks, intelligence is a measure in which we take immense pride.

Questionable, this intelligence.

We walk the same paths everyday rather than experiment with a new route. We lunge into our pockets if someone asks us if we took our phone or card. We assume there is a third example in this series, because who gives only two?

A great achievement for humankind is the slow and humble acceptance of the fact that we’re mostly irrational beings. That our decisions and expectations are justified by our deep-rooted desires like comfort or safety, and not the cold logic that we rationalise our actions and our thinking with.

What is it that we pride in, then?

Data, Information and Intelligence

Public transport is crowded. You notice that once all the seats are taken, people occupy the aisle and hold on, trying not to fall. The same aisle is also used by commuters to move up and down the doors to get off at their stops. This is data.

There are many things to absorb in this overwhelming environment. You are drawn to look at the aisle, where there’s a lot of bustle. You notice that here, closest to the front and back doors, is the most pull and push — the most discomfort. You are looking at a slice of the environment to infer from. This is information.

The next time you get into a crowded bus or train, you decide to head straight to the middle of the bus to avoid getting caught in the incoming and outgoing traffic on the aisle. This is intelligence.

Every mind — human or animal — that repeatedly makes decisions, uses data, information and intelligence to do so. To save time and act quickly, we consume data, filter it, and then file it in our ready directory of actions — or patterns — to deliver predictable results each time. It’s the only way we know to learn. Once a decision has been made and its consequences prove to be as expected, we store the pattern for future reference.

New commuters discover that even though they’re standing between doors in public transport, they could still get pushed around. Soon, they learn to maneuver around their tiny space to get out of the way of people getting on or off the bus. Soon, they aim higher. They can sense a soon-to-be empty seat in the fidgeting of its occupant. Those who form patterns manage well. Those who don’t, are pushed around and often get angry and upset enough to brawl with fellow commuters.

With observation and increased attention to results and their variations, we find that within big patterns, thinner, finer patterns emerge. This is our Grand Repository of Fine Patterns — our beloved, prided Intelligence.

The bigger the repository, the more intelligent one is. The smaller the repository, the more stupid one is. The Great Grand Repository of Fine Patterns — it’s what separates the people who manage to sit down from the angry dumbos who get knocked around at 8:30 a.m. on a Thursday.

They mostly seem like migrants.

A horrible, horrible bias.

Biases and Decision Making

But we must admit, we are pretty biased against biases. Without biases, we would be incapacitated; that is, if we managed to stay alive in the first place. We are biased against the rattle of a snake, smelly foreign food, burly men in dark alleys, and as unfortunate and sexist as these are, these are natural reactions towards self preservation.

Every moment, we are subject to a barrage of information and we have limited time to act. We would be paralysed if we had to make a decision every time we saw an insect with a sting or someone bigger and stronger approached us. Our overall intelligence is therefore just patterns, heuristics and biases that we have trained to work for us. This is default programming to avoid thinking, eliminate options quickly, and decide what to do or assume next. It’s literally in the word — to decide, where ‘cide’ means to end, to cut, to kill. That’s why we call murder ‘homicide’.

And like murder, biases, sometimes make for terrible decisioning.

At times, the brain reads a situation wrongly because it exhibits similarities to a pattern that it has already learned to respond to, like feeling disgust at a cake shaped like a turd, or fearing shadows in the dark in your own home. You know it’s chocolate, there’s nothing to hate. You know every corner of your house, so there’s nothing to be scared of. But these emotions — disgust and fear — stem from biases designed to protect us, but in another context. Repeatedly acting on these biases is detrimental to the Great Grand Repository of Fine Patterns, and in turn, to our beloved, prided Intelligence.

When we trust our biases in situations that we have mistaken for other similar looking situations, the finer patterns that we took time and energy to split are proved wrong. The pattern loses its nuances and the original context in which it was formed. It forces these finer patterns to collapse and fuse back into bulkier, less descriptive and detail-less blobs of information and they are labelled with fear, anger or disgust for easy access. Big. bulky patterns mean a smaller repository of fine patterns. We just got stupider.

But guided by fear, anger or disgust, we certainly got surer.

Intelligence is inferring more from a bigger pattern to find finer patterns. Biases are enforcing a set action pattern without examining and splitting it into finer patterns. Both attempt to put the world in context. Both are instructions to maximize predictability and survival.

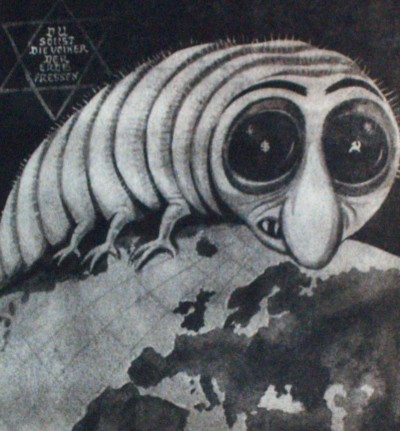

In ancient times, natives greatly mistrusted neighbouring or migrating tribes. Experience had taught them that these foreigners had different rearing habits and their livestock would bring in unfamiliar and dangerous diseases. They often introduced alien flora that would prove to be invasive and alter the natives’ crop yield. Worse, these migrants would often transmit diseases that they seemed immune to. It made sense then, to mistrust and disallow the mixing of tribes for the purpose of self-preservation.

This association of alien communities with weeds and disease has possibly genetically stuck on.

We see a similarity in Nazi Germany, where Hitler, a severe germaphobe, equated Jews to parasites that could spread disease in the German nation, and reasoned that they needed to be eradicated. The same holds for the Uighur Muslims, who are being sequestered into camps, dehumanized and associated with weeds that need to be cleansed of their impurities, like petty garden pests.

But we are not native tribes anymore. We are a melting pot of cultures, races and peoples. If we could relook at our biases, we would know that we are still perceiving threat in secure environments and distrusting normal things that only seem unfamiliar, but aren’t. With an inability to separate and refine data, our biases give us instructions that can no longer help save us. They only make us ‘biased’ against people and situations.

Which is why, all instructions, be it intelligence or a bias, must constantly be updated because the world in which we act upon these instructions, constantly updates. Revamping of patterns, or Bayesian Updating, is important for the health of one’s intelligence and biases equally. People do it. Entire cultures do it.

Today men can cry, children don’t have to be beaten to be disciplined and wheat is suddenly bad(?). In India, Sati and Triple Talaq have been banned. Slavery has ended. Saudi Arabia allows women to drive. Through 8000 years of doing things a particular way, these cultural organisms have updated their biases so that they can see the same thing that the changing world that they are a part of, sees.

Updating biases means opening our eyes to more information and finding finer patterns. It is the window to the truth and reality.

Which brings us back to Siva and his anger issues.

It was very difficult for Siva, Lord of Speech and the Truth, to accept defeat when he lost a debate. Imagine that. To lose a debate when you are the master of truth and speech. Words are your nuclear arsenal.

Yet, you lost your argument. Your reality was summarily reduced to an illusion. Your point of view was not accepted. If you were Siva, you’d be pretty mad, too.

Siva’s argument is the Truth. All the data. All the information. Not a slice of it.

For the truth to be seen, it must be welcome in our worldview, which is like a window to the world we live in. This window is only as big or as small as our Great Grand Repository allows it to be, and it only lets us look through the screen of our Updation-Phobic Biases.

We’ve all had our debates, yelling on the other side of these windows, wondering why we are not able to get our point of view across. It is frustrating. It is enraging.

Durvasa is born from this rage — an anger that wants the truth to come afront and be seen, even at the risk of destroying someone’s reality. This is why his curses are so potent. Durvasa is an embodiment of the truth. He does not tell lies. Which also means that when he curses someone, he is telling them the truth. When he curses Indra that he will lose his power, reality bends to make Indra lose his power, because Durvasa cannot lie. When he curses Sakuntala that her husband will forget her, her husband promptly forgets her because Durvasa said so, and Durvasa never lies. His words materialise into Indra’s reality, Sakuntala’s reality, anybody and everybody’s reality who he is angry with.

And he is angry with anybody who ignores him.

Durvasa, in all these stories, is a metaphorical stand in for Inconvenient Truths that refuse to be ignored just because we are blissful in a worldview built by our intelligence and biases. The Truth — the constantly updating world — will huff, puff, curse and fracture our realities unless we acknowledge it, give into it with eyes closed and open arms, and accept it into our worldview. Until we do, it will truly imitate Durvasa — One who is Difficult to Live With.